The book dedicated to

Monet Starr

Pam Simpson

And

Anna Eglitis

Your help and encouragement warmly appreciated.

Without that help there would be no book!

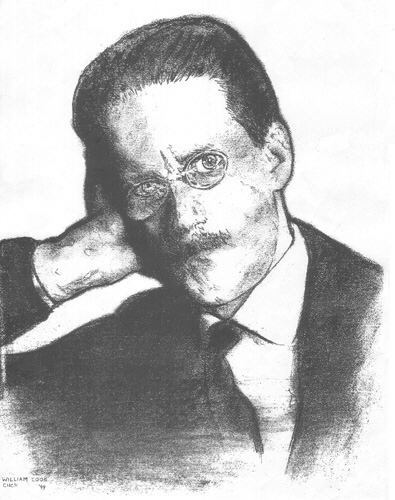

The sketches of Joyce by William Cook of

Wellington, New Zealand.

William is primarily a writer with art

and poetry as complementary interests.

Grateful acknowledgement is made of a grant

from the Cairns committee of the

Queensland Regional Arts Council; for

the preparation of the manuscript for publication.

“Bear with my weakness;

My old brain is troubled

Be not disturbed

With my infirmity.”

The Tempest

Shakespeare

A readable essay

On Finnegans Wake.

Indeed it is done

For Finnegans sake.

“Thought” is the “Word”

God bless my soul!

Each is the other,

And each is the whole!

Part 1

Note:

The author, the publisher, the keyboard

operators and the printers join in disclaiming responsibility for any misspelling

of Joyces invented words; for any misunderstanding of his grammatical experiments;

of his abuse of the vowels; his usage of punctuation.

All due care has been taken to preserve

the originals, but the economics of perfection prohibits exactitude.

We take refuge in Joyces own understanding

of such effort, his advice that “the words may be taken in any order”,

and “So why, pray, sign anything as long as every word, letter, penstroke,

paperspace is a perfect signature of it’s own?”

This decision justified by the fact of

a similar disclaimer was made on behalf of Faber and Faber in their first

edition of Finnegans Wake, 1939.

It is to be noted that the four

parts of this essay are but dimly related to the four parts of The Wake.

The small essays represent but daily readings, often at random, a page

by page comment altogether too demanding.

A brief note on the Joyce who

gave us Finnegans Wake.

This essay is no scholarly treatise, but

the observations of an ordinary reader, ‘The reasonable man’ of the Law

Courts; The man who is the very life of the publishing house, the man who

buys books for the pleasure of reading.

But that man has his mind conditioned by

exposure to the Australian ethos; a land so ancient that records of its

native people extend back by at least 60,000 years; so old that its mountains

are eroded down to low hills; its inland sea now dry; its rivers dying;

a land which gives birth and life to a strong and virile people; tested

by the smoke and heat of thousands of bush fires; hail stones of devastating

power; floods which savage vast plains; annual cyclones, all in general

terms the basis of the good life, beautiful beaches – modern roads and

decent, tolerant but tough citizens, well adapted to the diversity and

the rigours of the land.

Such the attitude of this writer when,

holding a copy of the Wake, (Penguin 1992) just glancing thru, at the mélange

of words, spotted, in plain English “Have I done it proper! Have I got

it right.” This phrase, from a man capable of ‘Ulysses’ spoke volumes;

he has written the maze of the Wake with purpose, and being well aware

of the extraordinary creative talent of the man; it was clear that the

Wake, following on Ulysses - a useless story, in one of his own puns

– could not possibly be ‘Unreadable’ – this a verdict of many influential

commentators, and so, bought the book.

Few of the commentators could have ever

attempted to read the Thing, for, tackled with determination it yields

rich treasure.

The present writer finds intimations of

deep human emotion and, or, feeling, in this enigmatic parody. Such findings

will be debated in the text; and will reveal a man so tormented in spirit,

that as with Prospero, “Every third thought is of the grave.”

Indeed, the introduction to the Penguin

1992 edition of the Wake, which has been the text for this essay; and by

a noted Joyce scholar, the Dean of a Faculty in English; boldly states

in his opening sentence that, “The first thing to say about Finnegans Wake

is that it is, in an important sense unreadable” – “it needs only to be

looked at rather than read.”

But the learned professor completely missed

Joyce’s plea for understanding; for Joyce was clearly aware of his early

impending death and hoped equally clearly for deliverance from the terrible

affection which was taking over control of his mind.

That he created this masterpiece of work

is a tribute; sadly written by himself; to the courage and tenacity of

the man.

His, “Have I done it proper; have I got

it right?” is a constant and poignant cry from the heart, even tho uttered

in the Irish idiom of his youth.

It seems clear that he knew, inwardly and

intimately, with certain conviction, that the Fates had him in eye from

his youth - for so the Wake tells us.

So having, by the aid of that vision imparted

to all good readers by those same Fates, or by the Old Gods of this world;

so having, early in my reading of this tragic valediction, gained an insight

into the tragedy of Joyces life, one was bound by ordinary human decency,

to let it be known; the experts are wrong – terribly wrong – Joyce’s Wake

is worth reading. That he made it difficult to read is his concern, but

it is a concern deeply crafted with a literary skill which we should –

and can admire; tho asking, at the same time – Why?

So now offered to the world, the heart

and soul of Joyce, encoded in Finnegans Wake, but there for only those

with; “Eyes to see and the heart to understand.”

The literary world has accepted the Wake

as Churchill may have described it; a puzzle, written in paradox, concealed

in enigma, the whole enveloped in mystery.

The exegetists have numbered the pages;

numbered the lines, the episodes, sorted out the hundred lettered words

and in general have created a mystique an hundred times more complex than

Joyces brilliant original.

But, the Wake, in essence is not thus.

Finnegans Wake is his valediction; the

tragic story of his last years; the story of relentless ill health; it

presents us with the true story of the writing of Finnegans Wake; settles

forever – or at least for the thousand years over which he hoped his work

will be read; the story of the writing of the book.

This aspect has two phases; the conception;

the planning; and the physical inscription of the text.

That such revelations are deliberate is

made clear in the text. As he says;

“Make no mistake, somebody

done it, and there it is.”

To which we may, if we wish add, his;

“Have I done it right? Have

I got it proper?”

He tells us; not very clearly, but

plainly enough that there are Seven Keys.

P 377

“The Key Keeper of the Keys

of the seven doors of dreamdory.”

‘Dreamdory’ – his house of dreams –

Finnegans Wake.

As with any bunch of keys; the key to each

door must be sorted from the bunch.

The location of such keys is indicated

in the following essay.

Similarly, the gist of the hundred letter

words is also treated with the touch of mystery and concealment, when he

tells us of;

“The clash of cymbals upon

the quivering reeds.”

This a very different signature from

that of;

“The thunder of falling

words.”

The myth that the book is ‘in an important

way, unreadable’ is a literary myth; and there is little doubt that such

was his intention.

But careful, searching reading reveals

a most powerful, touching, human story.

Such the power of his works, it may rival

that of Shakespeare. Certainly not one of the thousand or so books in print

about the work and the man have so far even glimpsed the true worth of

the man or his work.

Art, For Arts Sake

In Ulysses, his protagonist, Stephen,

is consumed, mentally – not yet physically with the problem of “Artistic

Integrity.”

Some unfortunates still ponder the intramysteries

of this self inflicted mental aberration.

There is no remedy for the affliction;

for it is but the product of the gravely serious tendency of the immature

adolescent to feel, and believe, and be deluded, by a conviction that his

thought process are of importance, or indeed have any relevance to the

real world.

Most sufferers grow out of the delusion;

there was a phase, happily a passing folly; in the period about the turn

of the 20th century, when some artists wrote “manifestos” concerning their

aberration; few read these declarations; they are now forgotten, though

in social histories of the times, such words as “fauvism”, “expressionism”,

“futurism” and other systems may be encountered.

The folly is however, not entirely dead.

Philosophy still waffles on about something,

as yet undefined, but called “realism” and Literature still accepts the

chains and restrictions of “Modernism” or, for the more argumentative “Post

Modernism.”

There are other “isms” but the root word

hardly matters; it is ever the argument which attracts.

The rest of the world does the real work,

whether it be Art or Literature.

Stephens “artistic integrity” tho not granted

the negative identity of an “ism” is not to be found in Joyces “Finnegans

Wake.” He came to terms with the “integrity” in the writing of Ulysses.

Joyce suffered a hard damaging life; the

daily grind of a poorly paid job in foreign places; shocking ill health;

and a life style which made consistent productive literature, almost, but,

the Gods be praised, not entirely impossible.

Simply put, Life knocked the nonsense about

“Artistic Integrity” out of him; taught him a few survival skills; granted

him the benefit; the ultimate blessing of half a dozen good and sympathetic

friends; and thus made his output, his lifes works, possible.

So Finnegans Wake is the real man; but

such the man; the mystique which drove him; that Finnegan is a puzzle,

hidden in an enigma, wrapped in a mystery; the ultimate singularity of

Literature, a paradox, deliberately fashioned to engage the attention of

the professors for a thousand years.

Genius?

He was no genius. This in the beginning

the dream of adolescence; later the claims of publishers.

He certainly had great talent; an amazing

vocabulary; an excellent memory; a reasonable grasp of the Romance languages,

and a fascinating way with words.

All these gifts of the gods, tinged with

the gritty taste of a sad descent from a secure childhood into the grim

distress of a gaunt poverty.

This unhappy life inflicted upon the Mother

and family by the folly of the father, spending the family fortune with

the publicans of Dublin and heaping disaster and ruin upon his family.

Thousands of men indulge themselves in the folly.

Joyce, as the firstborn lived thru this

descent into squalor; watched the growing folly of the father, saw deepening

despair of the Mother, bearing in all thirteen children of whom six died

in infancy before he left home in 1904, at twenty two years of age.

His mother gave up this unequal struggle

in 1903, and Joyce suffered, the rest of his life, the remorse of having

denied his dying mothers request for a prayer from the favoured firstborn,

and at that time the main support of the family.

Wise heads in the Church had noted the

talent of the child, and provided the growing boy with a free and thorough

education; this with the purpose of James entering the priesthood, but

after obtaining a pass “by grace”; his examination marks were dismal; he

renounced both the opportunity of priesthood, and his religion.

On June 16 1904 he met Nora Barnacle, red

of hair and bright of mind, and they fled Dublin to a teaching job in the

underbelly of Europe.

He tells this story in many ways, in broken

words and many tiny sentences, scattered thru both his books. ‘Ulysses’

which brought him world fame, a respected place in the literary world,

and above all, the means to live a better lifestyle for his Anna Livia

and his children. The Wake confirmed his place in the literary world.

His son did not inherit the fathers talent;

his daughter tho, had a rare talent as a dancer and artist, but slipped

into the terrors of schizophrenia, to the extent that she moved into permanent

professional care.

‘Ulysses’ brought fame, Finnegans Wake

became his valedictory; his book, his story, told in his own words.

It is essentially his personal book.

It was formally declared by the establishment

to be “unreadable”. This essay, and much other work, demonstrates that

“unreadable” is a literary myth.

That he ‘thumbed his nose’ at the literary

establishment; those writers who live to dissect the work of others, the

“sniffers of carrion” is now accepted. Beyond all criticism, the Wake is

his book. It will keep them busy for a thousand years.

For Joyces own perception of his college

and home life, his “Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man”, and “Ulysses”

are both good reading.

Finnegans Wake is 'Unreadable'

In the beginning, it was little more than

a simple disbelief that the thing was unreadable.

This the general opinion, expressed even

by experts.

The very first words to the introduction

to the Penguin 92 edition states, flatly

“The first thing to say about

Finnegans Wake is that it is, in an important sense, unreadable.”

The writer then offers an interesting

forty two pages about the book, and its author, James Joyce, so, it seems

that his first impression was a pretty general kind of observation.

So, looking deeper into the book the opinion

was confirmed that the book was indeed readable, but in its own way; it

is indeed difficult – teasing, grossly improbable, but probably, possible

and that – deep in the chaff, were grains of wheat, enough indeed, to make

into a decent loaf of bread; or more plainly that there was a deep and

serious purpose buried in the maze of word.

It is this purpose, which has been searched

out in this essay.

Readers quickly learn that much of the

thing does not require reading. It is, as he warns us “all false tissues”

“not one tittle of truth, allow me to tell you, in that purest of pitiful

fabrications.”

“It is a pinch of scribble, not

wortha bottle of cabbies, overdrawn. Puffedly offal tosh.”

“Flummery is what I would call

it if you were to ask me to put it in a single dimension what pronounced

opinion I might possibly orally have about them bagses of trash which the

mother and Mr Unmentionable (oh breed not his name) has reduced to writing.

_ _ _ _ !”

Thus we pass by the long formless paragraphs;

scan the word for the story revealed only in reasonable English.

These extracts are from the long pages

of talk about the book. All are identified by page elsewhere in this essay.

There are many pages of the book only lightly scanned; they are his broken

and confused rambling on history – long argument (presumably) on nothing

recognizable, merely inventions, providing a framework to introduce names;

these allusions provided to keep research writers busy. It is doubtful

if any such have yet plumbed the depths, or in any way exhausted the supply.

It is believed by some that the history

of Ireland, and thus of the world is hidden amongst those words; this on

the basis that the microcosm reflects the macrocosm; the individual is

the Universal; the particular, the general; or as Blake put it, “All the

world in a grain of sand.”

So, thus far, there is a readable book.

It is difficult. The writer of the book tells us bluntly that it is not

a ‘real’ book. We note that he is interested not only in reincarnation

but also in other Universal Matters. In Mythology, Life and Death; Black

and White; Man and Woman; War and Peace; Guilt and Remorse, the Particular

and the General.

Even the ordinary attracts him with simple

relationships; up and down, in and out; left and right, fast and slow,

hot and cold. We also note that all subjects, from the holy to the mundane,

are treated with levity – He makes mock of all things, but, sadly, requires

and commands thousands of words to say so little.

King Solomon wasted no words;

“Of the writing of many books

there is no end; but all are vanity.”

So here we are faced with close to

a quarter million words, of which the author himself is derisive; words

which confuse rather than enlighten; words which hint and provoke but conceal

the reality; high purpose reduced to laughter; revelation of eternal verities;

the beginnings of language; this seen as the “Original Sin” of Hebrew Theology,

and a dozen other arcane ideas are glossed over with broken words and linguistic

gymnastics; all to be the subject of involved explanation, by professional

wordsmiths.

The Work reminds one of so much modern

art; art which demands pages of words to assist the understanding.

So this essay treats the main theme; the

author of the work, Humphrey C Earwicker, in his several guises, and takes

a brief and “ordinary readers” look at the thing as offered to the public.

This rather narrow view is a natural reaction

from the reading of his earlier books, ‘The Portrait of the Artist’ and

‘Ulysses’. In both, the work is highly autobiographical; so the approach

to the “Wake” was much the same; What Joyce has to say about himself in

‘The Portrait’; is the story of the young man, the first flowering of a

rich talent as the man about Town, and the town, Dublin. ‘Ulysses’; the

mature man, loafing about the same town. In the Wake; surely not the old

man, sans everything?

But indeed the recurring theme, clearly

stated in both the opening and closing paragraphs is death, death defeated

and softened with the hope of reincarnation; and throughout the book in

all its chapters, it is not only himself, but the self and the chosen lover,

mother of his children and bearer of life – immortalised in his work as

Anna Livia Plurabella. The loved and lovely, river of life.

It was a fancy of Joyce that the Wake equaled

the magnificent 6th Century Book of Kells; a beautiful manual on the gospels;

hand drawn, and painted, and a National Treasure of Ireland.

This fancy, this belief, an ego fancy in

Joyce; an image in the ‘dreamdoory’.

The ‘Brave New World’

Much of the ‘mystery’ of the Wake appears

to be no more than a confusion of his mind; but this confusion very deliberate,

a dream world.

He lived in the years of the deconstruction

of the Victorian Age, its art, architecture; its science, literature; its

basic economy, and its religion.

The West was deserting the Church; Womens

liberation gaining public attention; physics was confronting classical

theory; art & literature and architecture confronting cubism, Art Deco;

realism and modernism. Poetry was flung out the window. Black versification

a poor, dark, introspective and ugly substitute; philosophy yielding to

New Age flights of fancy and a new look at ourselves and the world.

The Great Depression killed the economics

of the Industrial Revolution; Capitalism, and its grim shadow, Communism,

rapidly taking charge, and ably supported by the second World War.

Well, Communism failed miserably within

two generations; and the other, the principles firmly supported by a new

liberal society, is still flourishing, despite the many catastrophe theories,

and its ever present threat of inflation. Gaslight was giving way to electricity,

horses to motorcars, skirts were up; stays were out and silk stockings

and cigarettes were in. Of these stupendous social changes, and many others;

he noted little more than that TV killed telephony. Then back to Joyce.

But Joyce, though he denied the Church,

is still subject to its teaching. He is neither agnostic nor atheist, though

very disrespectful of God.

“Reverend; or should I say

Majesty.”

“O moy Bog be contrited

with melancetholy.”

“His gross the Ondt. O Kosmos!”

“Your Ominence, Your Imminence,

and delicted fraternitrees.”

“Rocked of agues, cliffed for

aye.”

There are many more, but none with

either reverence or respect for believers.

But that early Church instruction is still

alive, and adds colour to the story.

So with the old Victorian stability with

its bitter controls breaking down under the terrors of the Great Depression,

there was released with WWII, a vast seachange; the sudden understanding

that we must pull together; to survive; a new understanding of the power

and the opportunities of a more liberal society; a new appreciation of

social wealth; a new sense of the Unity underlying both Nature and humanity;

of such new thought; Joyce but glimpsed

“_ _ _ A Magnificent Transformation

Scene showing the Radium Wedding of Neid and Moorning _ _ _.”

But that’s about all. Just the flashes

of light from the old days!

He died before the first wave of the Baby

Boomers; never had a smile from the Flower People, nor read anything of

the New Age literature but had a glimpse of “the new woman, with novel

inside” odd, how she has blossomed; missed the vast exodus from the Church,

when, during those most terrible years of the Holocaust, the bombing of

the cities; so many pleaded, tears in their eyes, for help from the God

of the Hebrew and of Christ and the Churches. And that God either did not

hear, or did not care, so we left him.

So James wrote his valedictory from a mind

bedeviled with guilt, denied of hope; dogged with glaucoma, with depression

and probably dysphasia; and because he was too good a man and too good

a writer, to offer lamentation and complaint, gave us the Wake; a literary

singularity; an Irish jest at the Fates and at Life.

Every word of it in the mindset of the

days of his youth.

The Artist At Work

The Aeolus segment of Ulysses contains

a para which speaks of Blooms interest in the house of the Key(e)s.

In Joyce’s mind perhaps, the key to his

Book of Kells?

This is a long shot, but the suggestion

is there.

Also, Bloom has left his house key at home.

Twice is coincidence; three times speaks

of purpose; thus in the last segment, Penelope, of Joyces Ulysses; Bloom

having left the key at home, he must climb the fence and enter the house

by a rear door. This chain of inconsequent items to be used as a motif

in his Orange Book of Kells; the Wake.

Such the complexity of the human mind;

he surely had the Wake in mind as he wrote his Ulysses, his Blue Book.

In the sacred caverns of the mind allusions

and associations; cross references and recollections flow in fecund detail

within and without every creative thought, and Joyce has a mind wholly

consumed with word. His next paragraph!

“It is amazing to view the unpar

one alleled embarr two ars is it double ss ment of a harassed pedlar while

gauging all the symmetry of a peeled pair under a cemetery wall. Silly,

isn’t it?”

More that silly; it is deep and clever.

This dexterous play with words emergent

in Ulysses, and now starkly dominating the structure of Finnegans Wake;

the dozen or so variations of that name used throughout; all reasonable

approximations accepted.

We can trace, simply enough, the

development of his experience with word, the growing maturity thru the

successive books.

‘Dubliners,’ his first book, is the immature

work of the emergent writer; full of purple patches; his men and women

ever defeated. The stories dark, tragic; suburban folly, negative.

Then, the ‘Portrait’; a more skilled command

of word; but the agony of the Artist in conflict with life. But all is

not lost. Romance, desire transformed by love; starry eyes, and the wrenching

discovery of beauty. Thus his bird woman.

“He was alone – – near to the

wild heart of life. – – Alone and young and willful and wild hearted –

– and girls and voices childish and girlish in the air.”

“A girl stood before him – – alone

and still – – whom magic has changed into the likeness of a strange and

beautiful sea bird. Her long slender legs, – – her thighs, fuller and soft

hued as ivory – – .”

And so on – – a pretty little couple

of hundred words;

“Heavenly God! cried Stephen,

in an outburst of heavenly joy – –.”

Then in Ulysses, we are given superb

pieces such as the ‘Cyclops’ segment; The Wandering Rocks; the Scylla and

Charybdis segment; and Eumaeus; these in conflict with the ‘Oxen of the

Sun’; Ithica, and Penelope segments; in all these latter, Word – – more

and more out of control; the Oxen of the Sun; a salmagundi of English as

spoken over 500 years; Ithica 300 paragraphs of simple padding; and Penelope,

a vivid exposure of Joyces internal monologue, thousands of words; all

indicative of a failing talent.

This lack of control, the present writer

suggests, is dysphasia; a failure of the motor function governing thought

and the hand that writes. So the words pour out; and the hand writes as

the mind conceives.

The opening bars of this Joycean literary

curiosity are robust.

In a few words we meet Mister Finnegan,

an Irishman whose life is overshadowed with thoughts of death and reincarnation;

we meet Humphrey C. Earwicker, of Howth Castle and Environs; the first

of the hundred lettered words; these a mysterious configuration of the

alphabet, charged with significance; but this quality only rarely invoked.

We will have to keep an eye on these H.L.

Words; they will crop up in one or two different forms and in unexpected

places, and there may be outraged cries from those people who study the

Wake professionally, as to the eligibility of two or three of such words

as are noted here. These will be dealt with later in this essay.

It is claimed by some that the Wake embodies

a history of Ireland, of the world and of James Joyce.

This latter may be traced with the application

of some care in the wild fantasy of Word; for the Wake, as with both ‘Ulysses’

and The Portrait of The Artist as a Young Man; is autobiography with a

rare flair. But history distorted by irony; and little else.

It will both amuse and amaze, confound

and confuse, engage and enrage!

From P8, Joyce launches into a conducted

tour of a museum devoted to the Duke of Wellington. England claims him

as one of her sons, but, the Duke is an Irishman. One of so many great

Englishmen who were Irishmen.

It seems strange that Joyce who was himself

a peaceful gentle man, should devote pages of his book to the Duke, to

the Russian General, and give space and words to so many soldiers and warriors.

He was a literary man, could have filled

pages with lyrical prose on the Irishmen who have made England the world

centre of our literary heritage.

This surely a study for an expert. Swift

Steele Sterne, Berkeley Moore Shaw Wilde; these only who spring to mind.

There are others.

Later in these first pages we will meet

Mutt and Jute; two very talkative characters; be subject to his theory

of the “fall” into language, run into the second H.L. Word and H.C.E.

a flitting tenuous figure in and out of the story, elusive, but ever the

subject of words; and words; contradictory, allusive and illusive!

Later in Book I we will be introduced to

Anna Livia, the loved one; to Shaun and Shem; the two aspects of his intellectual

life; both voluble Irishmen. Through these he will tell all; Joyce says

elsewhere;

“Those are only beginners.” We

will, possibly, begin to frame an answer to yet another question he asks

of his readers, “Have I done it right? Am I doing it proper?”

Help!

Pages 103-125 of the Wake are

the usual flow of words, but crafted into them is the revelation that others

assisted him with the physical writing, and, of much greater interest,

with the composition of the Wake. These pages demand some critical reading.

It is recognized that this is a general

comment; the text though complex, tells the story, thus, the opening bars

at P104. For starters, we are told by Anna (Livia)

“The all maziful, the Everliving,

the Bringer of Plurabilities, haloed be her eve, her singsong sung _ _

_.”

This sentence suggests that Joyce was

aware of the New Age concept of God as Her, surely not “She.”

Then follow about two hundred book titles,

all apparently utter nonsense, followed by a paragraph of equally obtuse

nonsense but ending, in plain English. P107,

“Our social something bowls along

humpily, experiencing a jolting series of pre arranged disappointments

down the long lane of generations, more generations, and still more generations.”

This an Irish comment on life!

So, life is difficult; “Prearranged disappointments.”

But these first pages, 104-107 are but

a blind – padding; amusing, but add nothing to the real story.

“Say, baroun lousadoor, who in

hallhagel wrote the durn thing?”

This a plain question; followed by

a plain answer.

“_ _ _ _ That its author was always

constitutionally incapable of misappropriating the spoken words of others.”

He then calls on the women of the world;

“Mesdames; Marmouselles; Mescarfs;

Silvapais; this, if you please, then, all she wants is to tell the truth

about him; Kapak Kapuk! Don’t mix matters; he has to see life as it is;

Kapak Kapuk; there were three men in him. Nolan and Brown and General Jinglesome

himself begob.”

This a clear reference to the contributions

of Brown and Nolan.

And so on, but as ever, the few grains

of wheat in the horses nosebag!

Then also P113, picked out from the chaff,

“While the ears may be inclined

to believe others; the eyes find it deviled hard to believe themselves.”

– Tip

“We cannot help but notice that

some of the lines run north south; while others go east west.”

Does this not indicate different handwriting;

different writers?

“A cosy little brown study all

to oneself! – its importance in establishing the identities in the writer

complexes (for if the hand was one, the minds of active and agitated were

more than so.)”

Could hardy be more clear.

He then tells us that it is not necessary

to sign letters ;

“Say it with missiles then and

thus arabesque the page _ _ _ _So why, pray, sign anything, as long as

every word, letter, penstroke, paperspace is a perfect signature of its

own.”

The words speak for themselves, whosoever

wrote them.

Then more chaff, till we spot this most

cheeky comment.

“The father _ _ is not always

the man who brings home the bacon _ _ _.”

Then more – and more on this possibility.

So it is clear enough that when speaking

of parentage, he is dealing with words; in brutal short; others have had

a hand, and a word, in the writing of the Wake.

Experts in Higher Criticism will enjoy

the enigmatic constructs in these pages; then, still mocking, P116,

“If the lingo gasped between kicksheets

– were used by philosophers, churchmen and others!”

This surely means if the language of

this book were so spoken, no one would listen! If and when they did so

read, they would be shocked! Or does he mean the language, the pillow talk

of you, and I?

Then,

“So what are you going to do about

it.”

O dear!

Then on P118 yet another ambiguous and

provocative paragraph. Experts only! This para too long for simple understanding.

“_ _ _ Anyhow, somehow and somewhere,

somebody mentioned by name, _ _ _ wrote it _ _ _ O, _ _ yes,

_ _ but one who deeper thinks will always bear in the baccbaccus of his

mind that this downright there you are and there it is, is only all in

his eye. Why.”

And surely confirmed in;

“It is not a riot of blots and

blurs _ _ _ _ and wriggles and juxtaposed jottings _ _ _ we really ought

to be thankful that at this _ _ _ hour we have even written anything at

all to show for ourselves; _ _ _.”

And what does he mean, P122,

“The cruciform postscript _ _

_ carefully scraped away, plainly inspiring the tenebrous Tunc page of

The Book of Kells _ _ _.”

Surely this means the editing of contributions

to the dark pages of his book?

Once again, work for exegetists.

Then at the end he names one of the other

– the other is considered more fully in Part III of this chaosmos; but

the revelation!

“Kak, pfooi, bosh and fiety, much

earny, gus, poteen? Sez you, Shem The Penman.”

This is of course, just the view of

a general reader; the reasonable man; the chap who buys books for the pleasure

of reading; so much more satisfying than staring into a screen, whether

T.V.; Cinema; or Computer.

The experts may disagree but this chapter

seems a plain statement of fact, despite the exotic words; the interesting,

revealing simple fact that Nora, with others, have assisted in the writing

of his book; and this because of increasing infirmity within himself.

Then on P.123 we are presented with,

“Lastly, when all is zed

and done, the penelopean patience of its last paraphe, a colophon of no

fewer that seven hundred and thirty two strokes, tailed by a leaping lasso

– who thus in all his marveling, will but press on hotly to see the vaulting

feminine libido of those interbranching ogham sex up and down sweeps sternly

controlled and easily repersuaded by the uniform matteroffactness of a

meandering male fist.”

Now, this para is in plain English

- this often a hint of real meaning.

Some might well think of an Irish ungentleman,

breaching an honourable convention. ‘A man does not strike a woman.’

Perhaps however, it is no offense to Womans

Lib.

The penelopean patience – the patience

of Penelope, waiting those twenty years for the return of her husband,

may well be a Joycean reference the long seventeen years of the work; the

achieving of the last phrase, and paragraph of The Wake, this followed

by a colophon, no doubt offered by Nora, in Ogham, the ancient Celtic text,

for Nora, as was Joyce is Irish of long lineage.

Ogham is written in simple upright strokes

above and below an horizontal centre line, thus

So it seems Nora thought to write thus

on the last page of his – his – manuscript! Thus in expectant mood; finish

the book with a Celtic motif; but Joyce, supervising the work from his

basket chair says, simple and flatly No! and removes the colophon with

“one sweep of a meandering male fist.”

In plain English, a very definite NO.

Of course, there could never be such a

colophon, for it is his intention to return the reader to the very beginning

of the book; the last paragraph must, by a ‘commodius vicus of recirculation’,

return the reader to Howth Castle and Environs, the opening words of his

book.

No, there was no violence here; this was

a literary matter, and equally clearly, Nora was indeed an accessory in

the work.

Interesting indeed to examine the manuscript.

It might well show an Ogham colophon, struck out!

This small essay on Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker

provides an interesting comment on the special pleasure Joyce derived from

writing mystery and paradox into his work.

Through the pages of the Wake are scores

of usages of this sigla HCE, or h c e, arranged in three word phrases;

and all an amusing variety. Possibly H2CE2 is a nod to science.

The cognomen are used, not randomly, but

on almost every page.

Finnegans A Wake

The title of the book, Finnegans

Wake was a closely guarded secret until publication of the full book.

The work was produced in installments,

published in magazines, and under the name “Work in Progress”, the articles

appearing between October 1923 and 1939 when Finnegans Wake was published.

However, Finnegans Wake is mentioned on

two occasions in WiP

P 607 offers

“It is their signal -- -- to seek

the shades of his retirement, and tease their partners, lovesoftfun at

Finnegans Wake.”

And P 617 is a Joycean teaser!

“ _ _ _ Fing him aging, well this

ought to weke him up, to make him.”

The full paragraph should be read;

it is an intriguing Joycean puzzlejest!

“Impossible to remember

persons in improbable to forget person places.”

This is Finnegans Wake, aka Joyce,

strongly hinting, in both instances, that it will be only “at his retirement”

when “he is aged”; that this secret will be revealed, for the following

hundred words report a funeral, an amusing Irish funeral.

This segment, Part IV of the Wake was the

very first installment to be published.

Clearly Joyce had the end in view from

the beginnings!

A long seventeen years between its first

and its last; its back and its front; its beginning and its predetermined

cyclic end in which he returns us to a most unsatisfactory beginning.

HCE

There are many names for him; Mr Porter,

Old Foster Toster, Osty Fosty, Kevin, O’Conner Rex; a score of others:

in the beginning it is Bygmeister Finnegan, with his “Addle liddle pfife

Anna living at Howth Castle and Environs.

HCE is, at this time, “Haroun Childeria

Egglesberth.”

Humphrey C. Earwicker is a later intervention.

P480

“Hunkalies Childered Easterheld.”

P480, Also has

“Eece Hagios Chrisman.”

P481, offers an experimental specimen;

“Hail him heathen, Courser_ _

_.Eld is endall earth.”

Then follows one such per page until

P488, which moves into some very interesting pages about Brown and Nolan.

The phrase on P530 is noteworthy;

“Hotchkiss Culturs Everready.”

This surely a clear reference, historical

now, to Field Marshal Hermann Goering, Air Marshal of the Nazi Airforce,

who boasted,

“Whenever I hear the word Culture:

I reach for my gun.”

Hotchkiss was the name of an early

version of the quick fire repeating or machine gun. This seems to be Joyces

only comment on the terror eating at the heart of Europe.

P582 of Pt III

“Humphrey champion Emir.”

P583-4, is a frisky love scene; a ball

by ball fantasy, matched with a cricket match. Lovers, and cricket lovers

should read with care. Very frank, but the erotic disguised, not only in

flannels, but in Joycean art.

This cheerful peace finishes,

“Noball. He carries his bat. Ninehundred

and dirty too. Not out.”

Is this segment a comment in Joycean

Irish on Don Bradman?

P586 presents us with the probable printers

error.

“Non---Coran---Ex.”

This should surely be “Hon” - would

it be humanly possible to set the Wake in type without some of those printers

devils, the typo?

P589 is another Joycean tidbit

“Elsies from Chelsies.”

Take the ‘lsies’ away from Chelsies

and we have Che; clever. The best of his very clever play on words.

P590

“Honoured christmastyde easteredman.”

Two Christian festivals in three words!

These last pages of Part III are mildly

erotic in Joyces dreamworld; but as to why the emphasis, the repeated use

of these initials, other than to say that this is perhaps Joyce himself

dreaming of his Anna Livia? Or is the repetition simply an ego thing?

Part IV moves into a different mode.

“Eireweeker to the whole bludyn

world.”

That which follows is indeed Irish

in idiom and no doubt in thought .

The sigla found in P593

“Haze see east _ _ _.”

The ‘see’ for C is plain to see. Thus,

page by page the witty constructions; thirty witty phrases extracted from

thirty two pages!

P597 offers,

“Heat contest and enmity.”

P603 is clever,

“Hyacinssies.”

P604

“Higgins Cairns and Egan.”

P613

“Health chalce and endnessessissity.”

P605

“Highly charged with electrons.”

P619

“Erect, confident and heroic.”

In the remaining pages of this saga,

he is leaving this world; the word becomes a lament; then hope emerges

from the doubts, and he dreams of reincarnation; envisages a past life

more worthy of him than this life, but in the unremorseful end he returns

us to the beginnings of his book yet again.

So, back to the beginning, and we find

there that HCE, is Jarl van Hoother or Harold or Humphrey Chimpdon.

The origin of HCE and Here Comes Everybody

is revealed in pages 30 to 32. An interesting story. P32

The great fact emerges, after that historical

date -- -- -- all the holographs initialed by HCE, -- -- -- only while

he was -- -- -- the good Dook Umphrey -- -- -- a pleasant turn of the populace

gave him a sense of those normative letters.

So, something happened, “a pleasant turn”,

“a great fact emerged” and HCE, up until now the spice of his imagination,

became HCE, Here Comes Everybody.

This “pleasant turn of the populace” was,

it seems, a political cartoon of Prime Minister Gladstone, by H.E. Childers,

the cartoon telling of Gladstone, as “Here Comes Everybody.”

Joyce would immediately see the happy coincidence

of his sigla; the name of Mr Childers and the mocking Here Comes Everybody,

and hey presto; a literary character fit to endure a thousand years.

But this simple explanation offers no satisfaction

regarding the heavy use of the phrase throughout the Wake.

Any intention; never revealed, and seemingly

impossible to trace. This usage, can be noted throughout, but this

randomly.

This simple question, Why, to be asked

of many parts of this enigmatic work.

A Family Affair

There is an intriguing couple

of lines on P125

“Maybe growing a moustache did

you say, with an adorable look of amusement.”

In the well known picture of him C.1904,

Joyce is a fine upstanding young Irishman, sans moustache - in the equally

well known photograph of Joyce with Sylvia Beach, in her shop in 1922,

there is a most handsome moustache, Sylvia had successfully arranged the

publication of Ulysses, with a French publisher. There is a good photo

of the pair in her shop – she alert; he dapper, with bowler, cane and moustache.

This young lady deserves a better place

in literature than Joyce granted to her.

Without Ms Beach, and Ms Weaver, who supported

him most generously with cold cash and publication of Work in Progress,

and Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap, who risked “The Portrait” and “Ulysses”

in America, and Nora Barnacle, his partner, mother of his children and

his life long benefactor; without these women, neither Ulysses nor Finnegan

would have been either completed or published. This comment appears to

be beyond any contradiction. Sylvia Beach tells us, “At least one third

added during the printing process.” His magazine publishers ever demanding

work to meet deadlines.

But this is a digression; the moustache

appeared sometimes during childhood of his daughter Lucia – the “adorable

look of amusement” this surely because of a word, a comment by the adored

daughter.

No doubt the experts, the serious students

of Joyces life will be able to better pinpoint the arrival of the fuzz.

We may well wonder as to what Nora said!

No doubt it added a trifle to that long

upper lip of the Irishman and here it is, clearly a happy memory, recalled

in the wild chaosmos of the dreamworld of the Wake.

As with scores of other events and recollections

in this wraith dream, the innocent comment, the “adorable look of amusement”

betrays the very human man behind the words – and he is well aware of the

disharmony throughout the work.

Now if this is not sufficient, the dreams

in the Wake, or rather the dreams of the Wake resemble all to closely,

the same intellectual carefully crafted pages of ‘internal monologue’ of

Ulysses; and this in turn reflects the long impossible introspective paragraphs

of “The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.”

Most of the potential readers asleep, the

book closed by P19; thus Ulysses!

The style – long long paragraphs of involved

introspective speculations of the immature adolescent. And sadly, such

paragraphs given free rein in the later work.

Thankfully, there is reason and purpose

within the spate of word. The verbosity has a backbone.

Many happy recollections, such as this

“adorable look of amusement.”

The Wake – which is a dream, is the story

of his fight against depression, against blindness; against his growing

dysphasia; the terrible afflictions of his daughter, Lucia, a victim of

schizophrenia; and his daily struggle, to “write a word a week!” It might

well be “weak”.

This man Joyce had more to bear than most;

but carried the load with an infinite courage, lightened by much Irish

wit and idiom, and, brightened somewhat by a rather shaky hope of reincarnation.

Indeed, in the last pages of his book the

hope of return is clearly stated – a return home, before being recalled

to another round on this most beautiful planet. So it is time to meet again

with his stormies, with his haughty Niluna, his wild Amazia; truly this

is a dreamworld. Few of us have any such recollection of a past life!

With him he will take, never to be forgotten,

that adorable look of his loved daughter.

Perhaps he is right – now that there is

neither Heaven nor Hell to glorify or damn any future life; we humans,

who deeply and instinctively, know that we are immortal, will now accept

in lieu of old gods, the hope, if not the promise of reincarnation.

Or, sadly, is this but another intellectual

cry against the utter finality of death, where there can be no memory of

love or of life. Nothing; nothing at all.

The plaintive hope of Elisabeth Barrett

Browning, that

“I shall but love thee better

after death.”

Or Christina Rossetti with her sadly

realistic,

“Haply I may remember, and haply

I may forget.”

Or the American lady – who, as the

carriage containing her now useless body passed by; noted with pleasure

that,

“The horses heads were turned

toward eternity.”

Every scrap of waste; bodies, ordure

– everything in land sea or air is returned to Mother Earth again, to be,

in her good time, returned to life again.

So what then of the human spirit – in what

form may we – you and I, ask, in what form shall we be born again? Surely,

as the physical is recycled; so will be the spirit? We may but speculate!

It seems clear that Evolution, or God,

for believers, or Gaia, has been intent from the very beginning to bring

into being, a high level of consciousness; the human animal the first to

have self awareness, or self consciousness. Such exists in only an immature

state in some mammals.

With ten billion years of life for planet

Earth, there seems to be ahead of us the possibility of a creature with

infinite consciousness and if consciousness, surely personality; as a wise

old Hebrew poet observed “In that day we shall Know, as we are Known.”

And that consciousness recycled again through countless lives.

What hope, what trust can we place in these

vague thoughts on reincarnation; to see again, in another face, another

time, another place, “an adorable look of amusement.” So may it be, ye

Gods; as he asks on P358 of his weirdword.

“Qith the tow loulosis and

the gryffygryffygryffy at Finnegans Wick _ _ _ washed up whight and delivered

rhight _ _ _” and so on.

This appears as a fair comment on our

understanding of the mystery of reincarnation.

Forever and ever amen!

Literary Notes

There are many fascinating aspects

in this reading of the Wake.

The first, is, of course, the reading;

for most pages are just a task, but then, there comes an understanding.

A paragraph stands clear – and with understanding follows always a flash

of pleasure.

Much adverse publicity was stirred up when

Ulysses appeared as installments in literary magazines, the Egoist in England

and the Little Review in America.

The episodes were first banned; the book

when published also banned in both countries. No English publisher would

look at Ulysses, so Ms Sylvia Beach, whose bookshop in Paris provided friendship,

encouragement and coffee to expatriate writers in Paris, provided much

more than encouragement; she found cash and a French publisher, who possibly

had little idea that he was producing the most controversial book of the

century.

By the time The Wake was published, censorship

of Ulysses had been lifted, first in America and later England; the American

judge noting that Ulysses was “Offensive rather than obscene.”

The Wake also found little favour with

publishers; there is little doubt but that it was published, as it were,

on the shoulders of Ulysses. It was immediately described as ‘unreadable’,

a poor judgment by the critics; and also it seems by many of his friends;

for the judgment still carries weight; the work has had very little success

in the literary world, other than the association with Joyce, and it seems,

in the Universities.

It would be interesting to know what the

staff thought as the work passed from publisher to editors, to typists,

proof readers to compositor and printer!

The manuscript would not go to compositors?

A terrible task to read and check those sadly abused words, and Joyce’s

handwriting was by now almost illegible.

How was it possibly edited? With Joyce

at elbow? Who checked the spelling of those exotic words? The hundred lettered

words? Who did the proofs; or perhaps they did not bother?

Enough to frighten the linotype machine

out of its wits! And what of the operator?

Or did Joyce give them an open hand? Free

rein with his words. He suggests this; on P121?”

“Indicating that the words which

follow may be taken in any order desired;”

But this is but a dozen or so words,

buried in a vast paragraph of about 1500 misused words; amongst which we

note.

On P118

“_ _ _ Gossip will cry it out

from the housetops, _ _ _ _ every person, place and thing in the chaosmus

of All e _ _ _ _ as the time went on as it will, variously inflected differently

pronounced, otherwise spelled, changably meaning vocable scriptsigns. No

it is not _ _ _ _ an ineffectual whyacinthinous riot of blots and blurs

and bars and balls and hoops, _ _ _ _ it only looks like it, and sure _

_ _ _ there is a limit to all things, so this will never do.”

These few words extracted from some

four hundred, all on the same theme.

He offers this lighthearted comment on

his own work.

“That ideal reader, suffering

from an ideal insomnia _ _ _ Calling Unnecessary Attention to the text;

_ _ _ errors and omissions.”

This entire chapter V of Part I (P104-125)

are such an apology for the work, its writing and its imperfections.

So from this comment may we infer that

the printed page is not exactly that which he wrote? For even the writing

is suspect for, in this same paragraph he notes

“Passing with a frown, jerking

too and fro, flinging phrases here, there.”

Also noted

“Throughout the papyrus

the revise mark.”

He knew full well, the trouble he was

causing, for he offers sympathy to

“That ideal reader suffering from

an ideal insomnia; all those red raddled obeli cayennepeppercast over the

text, calling unnecessary attention to errors, omissions, repetitions and

misalignments _ _ _.”

Unnecessary attention to his words?

So it’s possible that the typesetters had a free hand; with his consent.

“Fuddling fun for Finnegans sake.”

There is a real sense in which we are

unable to express our deepest experiences. Words are not enough; for some

experience there is no word.

One simple instance, experienced by many;

to watch the moon rise above the edge of the sea. This brings a silence

to so many; something so far beyond self as to deny word to express the

emotion. Another striking and beautiful instance is that most marvelous

picture of Earth, blue and white, taken from the moon. It silences most

who see it!

Climbers, mountain men know this - it is

greater than the self; that view of mountain tops above the mist, the vast

reaches of hill and valley; some may say “wonderful” but the others are

silenced by the sense of that which is so vast; so deeply beyond our self.

We feel a unity with the universe, sense

the life flow in self, in the trees, the thousands tints of green - have

an awareness of the life in those trees; the flow of the life in the little

creatures, the streams, the lakes spread out below us, a strong realization

of the oneness, a glimpse of the thing we call eternity; a startling sense

of presence, and it becomes easy – simply, to say, when that splendid moment

fades, and speech is again possible.

“All this I am

All this is part of me.”

Most of us come down from the mountain

a little more wise than when we climbed, all with an experience never to

be forgotten.

We have a word for this experience; the

word is “ineffable” but this word, like all other possible word, only approximated

the ‘experience’ this is felt only in a deep emotion, deep beyond word.

Joyce attempted to enter this experience

in Ulysses. He attempted the task through pages of words attempting to

record the dark stream of that subconscious dialogue, in which, endlessly

it seems, we talk with ourselves and imagined advocates.

The words will flow unrestrained, if we

allow it; the experience common to all humanity another aspect of the unity

in which all exist.

Joyce gave Molly Bloom, in the Penelope

episode of Ulysses unrestrained access to many pages, in one full, flowing

stream of monologue but to little avail. Few indeed can manage it.

The observant reader, after only a page

or so will say; “This is not what Molly Bloom thought. It is only what

James Joyce thought she thought.”

It is the same with all experience, whatever

words we use to describe it, the simple blunt truth is, that words cannot

tell – all experience is an emotional adventure; the words ever an intrusion

on the reality.

“Wonderful” “Marvelous” do not convey the

depth of aroused feeling. “Nothing like it,” is banal.

This strangely raises another indicator;

all the world intuitively recognizes that the body is a separate entity

– ‘My’ body.

The “my”, the “me”; the “I am”; stands

always beyond – as Joyce says in one of Stephens interminable monologues,

“I seem to stand apart from

my self, a little behind.”

An experience shared by many; perhaps

all of us; unique and alone in the universe.

This a slightly different aspect of our

story but New Age spiritual teaching of this duality, which is separation,

is very plain, and to enjoy a full maturity as a human being, a sentient

creature; this duality must be resolved – “I am” is; ‘I Am’, never a duality.

We have been in touch with the Life, the

Spirit, call it what you will; had a glimpse, momentarily of creation;

sensed a unity with Life itself, and it is utterly beyond us.

“How can words say what

love is. Words speak for the aching heart.”

As with the Wake, Joyce has a dark

story to tell; but his words, even the words of Shakespeare are not enough;

so he invents words, but ever the words stand, stark, dead; a sorry expression

indeed of that which has so stirred his spirit.

We say – yes, a good trip - wonderful –

other superlatives, but the experience is treasured in the deep of the

mind forever.

Such is the human mind that even in our

fading years, it is still possible, in reverse, to relive that rare moment;

to be young again and above the clouds, beyond ones self, for a glorious

moment, a never forgotten experience.

Joyce seems never to have had this lovely

experience; no silence here; just the intellectual babble of words. Word

used with deliberate purpose to tell the deeply personal story of pain,

frustration and the driving determination complete the work, and to hell

with the critics.

It has been said, and so true is it, that

the underlying principle is now accepted as an axiom of Chaos Theory, that

the flutter of a butterfly wing may ultimately create a typhoon half way

around the world.

This principle indeed a very real aspect

of nature.

Some smart mind noted it early, when in

1775 he said “The shot fired in Concord will reverberate round the world.”

That shot changed the world, sent history

reeling down a new pathway; created the great USA, and initiated vast changes

in human affairs; not yet come to an end, her children working in deep

space; planning a living community on the moon.

As our Chinese people say, ‘We live in

interesting times!’

So with James Joyce. He has a dream -

so do the rest of us; but Joyce did something about it; turned the dream

into his “dreamdoory,” his dream story, a well crafted welter of words,

crafted into a little book, Finnegans Wake; “A word a week,” “Writing when

he felt like it,” but in the end a book is, like the bullet or the butterfly

wing; making its way round the world.

Firmly entrenched in University; Google

and other search engines, hundreds of chat shows, and, who knows; may be

studied on Krypton or some other planet in some other world, such the magic

of the Web and the Internet.

The thing which permits that shot to be

heard in China, is but the Unity which underlies all living things in this

world, and we should be exploring the possibility that such Unity also

activates other worlds; that our contact with them will not, cannot be

any space ship, but will be thru the contact of minds, their minds and

ours, operating on a common vibratory rate, or perhaps, to be more acceptable,

a common wavelength.

But this is a digression; springing from

the remark about a butterfly wing!

Joyce also noted the principle; his observations

based on the understanding of “The universal in the particular; or the

history of Ireland as a pattern of world history, why not indeed, is not

the author and creator of both histories, those of Ireland and World, but

man?”

Man has created both of these illusions.

Blake put it nicely with his “See the world

in a grain of sand.”

The unity is but the composite of the infinitesimal!

There is another thing! Did he remember

Shakespeares Macbeth?

“Nature seems dead and wicked

dreams abuse the curtained sleep.”

Nature seeming dead, simply because

the Wake is a dream story; the wicked dreams; the impish perversion of

word in the dreamdoory; curtained sleep, of course, Nora and the children

asleep in their beds, James “creaking” jokes about the literary world,

busy indeed, at producing “A word a week,” though in fact his work was

much better than that.

The Wake was first published as installments

in certain literary magazines; and as all writers will know such work is

dominated by the dreaded ‘dead’ lines, the last day possible for publication.

Miss the deadline and you’ve missed the chance. So by his editors insistence,

this butterflys wing was brought into existence and has deeply troubled

the literary world since. Just another instance for Chaos theory.

On The Writing

Yet another of those interesting

little notes which make the Wake such a challenge.

It is often debated not only Why – but

How and Who cobbled the book together. This problem is fully debated in

the pages 104-125.

The pages are full of stardust or whatever

the padding; you are offered the choice of P114

“Sand pounce powder drunkard paper

or soft rag _ _ _ _ the teatimestained _ _ _ _ is a little brown study

all to oneself, and whether it be thumbprint or just a poor trait of the

artless, its importance of establishing the identities in the writer complexus

for if the hand was one, the minds of active and agitated were more that

so _ _ _ _.”

There follows a cryptic comment that,

“It doesn’t pay to sign letters,”

“So why sign anything so long

as every letter, word penstroke, paperspace is a perfect signature of its

own.”

Surely these words tell us several,

writers, copyists, stenographers or whatever, are contributing to the text;

collaborating is a word he uses.? Telling us also, with scarce veiled mockery,

on P115 that

“A true friend is known much more

easily, and better into the bargain, by the personal touch _ _ _ _.”

In plain English, the more canny (observant)

amongst you will be able to detect who wrote which, by the style, the ‘personal

touch.’

These pages carry, within the verbose waste

of words a clear, tho, concealed message. Others have assisted with the

work.

One, no doubt debatable construction, surely

that in his cosy brown study, one if not several writers, writers who shall

not reveal their names, have added their parts to the whole?

In these few pages the queekspeak is volkspoke

in verdant verbiage and the pathways thru the undergrowth are overgrown

with bushlawyer and reveal concealment.

But those pages speak softly – secretly

with glimpses of the hidden snakes, lizards and bandicoots in the undergrowth,

then P.112

“ _ _ _ The meaning of every word

of a phrase so far deciphered out of it _ _ _ we must vaunt no idle dubiousity

as to its genuine authorship _ _ _ _ but one who sees deeper _ _

will always bear in his mind that this downright “There you are,” and “There

it is” is only all in his eye.”

Why? It sets the mind at a dyssicult

ask.

It was indeed, in a moment of doubtful

uncertainty, that is seemed proper to attempt an essay on some understanding

of Finnegans Wake.

Understanding, in the book, is a dream;

the picture of Joyce which emerges in that dream is somewhat like the engaging

picture of Joyce as seen by Caesar Abin on the cover of the Penguin copy

used by this writer to quote from the Wake, and what better authority?

P114

“It is seriously believed by some

that the intention may have been geodetic, or, in the view of the cannier,

domestic economical. But by writing thetherways, ent to end, and turning,

turning and end to ent hitherways, everything and with lanes of litters

slithering up and louds of latters slithering down, the old cometomyplace

and japetbackagain from them. Let Rise from Him Lit. Sleep. Where in the

waste is the wisdom.”

Was there a split in the infinitive

somewhere?

Kipling told us that every possible human

question can be answered by the use of only six questions.

“I had six honest serving men,

They taught me all I know.

Their names are What and When and Where,

And Who and Why and How.”

It is suggested that we know Who; and;

What. And When and Where.

So “Why” is a good question, and “How”

another.

Both probabilities looked at within this

essay, but, please note, not by any literary critic, nor a professional

exegetist, but a plain ordinary and reasonable fellow, interested only

in good reading, and who, quite properly, assumes that since Joyce wrote

the thing he intended it to be read.

Yet, it seems impossible that an extremely

talented one, as Joyce was, would spend 17 years of his life, and produce

so great a flood of words, new, old and in between, to produce an unreadable

book.

We imagine it to be readable, and quickly

discover how to so read. A glance at the pages shows us, equally clearly,

that the reading will be difficult.

It is rather like Stephen Hawkings, “A

short history of Time.” The opening statement is interesting. But the arguments

to prove this statement but add to the confusion.

Thus, the Wake is difficult, but not “unreadable.”

As the short history of time has demonstrated, difficult is by no means

impossible.

The following pages should convince any

reasonable man that there is something worth searching out in the Wake;

and the findings will stir the heart.

The writer has but dipped more or less

at random into the word fest; so much of it unread, but some direction

and some interests has been gleaned.

We do not put our Agatha Christie down

because it is difficult; nor ignore the weekly crossword.

So, the first work was, exploratory; a

turning of pages at random to assess the task.

It was a surprise to note that much is

written in an idiom, which, though irregular in an Irish way was legible

and reasonably plain English, but treated so surely, so deliberately

as to become vague in meaning. There is a message hidden within the exotic

flood of verbiage.

This verbosity so clearly a deliberate

imposition on the basic ideas, as to make it equally clear, that to read

sense into the text one must ignore the extraneous words, so, one must

thin out the forest so that one may see the trees.

Such is the method used to read the Wake.

Examples offered throughout in a very brief

sampling of the work, reveal a rather impish mind; disrespectful of society

in general, and many of the ‘sacred cows’ of society; quite prepared to

make history conform to Henry Fords definitive; “All history is bunk,”

this reduction ad absurdum seems to include the history of Ireland; a seeming

contradiction to his confessed intention of finding the “Soul of Ireland,”

for the world.

He has a fixation of mind regarding the

beginnings of language, together with a deep misunderstanding of the function

of language; he draws four of his most voluble characters from the heart

of the New Testament, this in sharp contrast to his early references to

the first five books of the Old Testament; he displays an adolescent and

sadly immature concept of women; in history and in our daily life; his

protagonist either believes in, or just hopes for reincarnation; but he

offers neither learning nor exposition on that ancient belief.

Sadly, he has nothing to offer on the incredible

burden which both law and war place on the weary shoulders of humanity.

However, pages 572-576 offer a rabid or ribald case to consider. Todays

lawyers would make millions from it.

Memories of his childhood flow thru these

pages Humpty Dumpty; and other childhood rhymes; echoes of John Peel with

coat so grey, and other ballads and songs; a few words on early films,

black and white of course, Charlie Chaplin and the like; he notes the advent

of radio – of T.V. but nothing of which he recalls will satisfy the social

scientists of tomorrow.

In brief, we appear to have a man suffering

from glaucoma and some form of depression, a willful, impish and compulsive

obsession with words; an extraordinary memory; a richly inventive imagination

and an impressive talent; a talent such, that many reputable literary critics

have granted him the accolade of genius, but as the Wake displays, a sadly

abused and deeply distressed genius; genius, perhaps reduced to talent?

This entire section of the Wake chapter

V of Part I; is written in reasonable language; clearly different in style

from other sections. It is essential reading for any understanding of the

Wake.

The Mind Alight

Reading the Wake, brings to mind

“Grays Elegy in a country churchyard.”

“Full many a gem of purest ray

serene

The dark unfathomed caves of ocean bear;

Full many a flower is born to blush unseen

And waste its sweetness on the desert

air.”

Thus it is with the Wake. Within the

dark unfathomed paragraphs are gems, the deserts of vain words offer a

flower, a fragrance, a bird, the bird ever on the wing.

But all such must be searched out.

There is however a simple key. Search out,

usually at the end of a paragraph, the few words offered in reasonable

English; sometimes no zany words at all.

But the bulk of the Wake is the desert

or the dark unfathomed.

There is much in the human make up, the

matrix of emotion; of response; of observation; of understanding, and creativity

that no man has yet; fully explored the depths. Neither poet, writer; philosopher

or priest; neither analyst nor alienist; none have yet made the ultimate

statement on the human mind.

Joyce, and the Wake also fail the task;

the impression given is that Life is a cosmic joke: But be not deceived.

Many, with a wider perception will be aware of serious purpose; so much

misunderstanding between us even in simple things;

“I thought you meant;” or

“I see it this way;” or, “But don’t you think.”

Such simple basics have spawned thousands

of books; the Wake but adding to the number.

The simple explanation the best; the reasonable

statement as defined by Occams Razor.

But not of Finnegans Wake. Education, which

is but the understanding of words and concepts has also failed in this

book. Joyce fails the common man in this despite his insistence on the

importance of word.

University and the high school children

will fail if the instinctive learning at Mothers Knee, the discipline of

the home is not learned. It is in the home that we learn the principles

of family and social life, the understanding of our personal reality. This

is the place for the concepts of security; love and confidence to be learned,

the Ten Commandments of Life.

It seems clear, from his life and every

one of his lifes works, that such confidence and sense of security were

lost to James, as the love and trust of his father were destroyed; in the

conflict with his mother over religious practice.

The Wake is the product of that deep insecurity.

A vast tirade against insecurity; depression and confidence in ones self;

the cold intellect at war with the restless ever dissatisfied spirit.

Humour, yes; courage; yes; a zest for life,

yes, indeed; all rampant in the Wake, but the underlying themes come from

the dark side of the mind; the certainties of faith now but hope; and as

the Greeks well knew, hope is indeed a poor need on which to rely for any

achievement.

So apply Occams Razor to the text of the

Wake. Ignore, as best as can, the wild words, the duplicitous paragraphs,

the play with words; seek out the sentences writ in plain almost honest

English; thus of say ten pages we rescue but fifty words, it is they will

carry the theme along.

This is the key used for the compilation

of this essay; we derive only a few underlying themes, but sufficient to

demonstrate the validity of his book.

The first mentioned is that of reincarnation;

you’ll beginnagain Mr Finnegan; then a long, to be continued, comic history

of the Duke of Wellington, sadly confused with the wider world, all supervised

by himself.

Then as a motif, the story of the writing

of Ulysses and the Wake. The Portrait not mentioned!

Then there are his ideas on the supposed

“fall” into language, this a poorly argued thesis. Not at all PhD level

by an Irish mile. The Wake, almost unreadable, reflects these ideas.

Then, a constant feature from beginning,

is his fixation with young women. Girlies, pipettes usually; this

sexuality has a slightly offensive influence over the text. It seems the

product of immaturity; an attitude irretrievably embedded in his adolescence.

The offense, intended or implied lies in the immaturity. The impression

created is that the man never enjoyed a mutually satisfying relationship

– experience in plenty – but little of any lasting pleasure; no depth.

There is another strange fixation with

some obscure Russian general. Another with Bishop Berkeley, a 16th century

cleric with advanced views on optics; perhaps his glaucoma is the bond.

Then there is the story of the writing

of ‘Ulysses’ and the ‘Wake’ as told by Shaun, the optimist, and Shem, his

‘alter ego,’ the penman and the pessimist.

There is a curious familiarity with the

Church and that other Book. On the second page he tells us that he knows

of the first five books of the Bible, but he rarely gets past the titles.

Later in the work he involves the four evangelists, Matt, Marcus, Lukes

and Jonathon, with variations, but we learn little from them, but their

duels with words are marvelous!

Through the work there is constant patter

over Anna Livia, sometimes Plurabella, the River of Life. She becomes a

totemic reference in many guises. She is wife to Humphrey C Earwicker;

the protagonist; the A.L.P. of the story. She is the women of Ireland,

but lower class – washerwomen; and flighty!

She graces the word with the few phrases,

the old paragraph of beauty, is ever the motif for the recurring life;

the reincarnation of which, in the last pages, she tells us; of his strong

recollection of past life, the wild Amazia; the haughty Niluna; so he slips

away confident that as Finnegan he will live again; and amid memories of

that lost life, he dreams of our eternal hope of recurring life.

In our day a courageous Pope has declared

in a Papal Bull that Heaven & Hell are but images of the human mind.

There is, and has never been any existence of such; so poor lone humanity

turns to reincarnation as a residual hope; for the belief is expressed

in the Upanishads long years before the Church gave us Heaven and Hell

as disciplinary encouragements to behave.

So, the end returns the reader “By a commodius

vicus of recirculation,” to the very beginning, “Riverrun, past Eve and

Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, to Howth Castle and Environs.”

Throughout, apparent unconsciously, is

a regret of the early loss of faith.

On P381

“ _ _ the beautification of the

degeneration by neuhumorisation of our kristianization.”

Despite these words the early childhood

teaching of the church never far from his mind. The apostasy ever an accusation

in his mind.

On P231

“_ _ it was soon that he, that

he rehad himself. By a prayer? No, that came later. By contrite attrition?

Nay that we passed. Mid esercizism? So is richt!”

Then, at last P368

“The finely ending was consummated

by the completion of accomplishment.”

These words an early anticipation of

a later event.

At the beginning, it is a good thing to

give some attention to the cover of the Penguin (92) edition.